A Common Language for the Innovation Ecosystem

Commercialization and Ecosystems Series (Post #1)

Everyone reading this is part of a massive commercialization ecosystem - a vast, amorphous, and complex network of interactions aimed at bringing better solutions into the world. The ecosystem is defined by the interplay of university and lab researchers, federal, state, and local government funders, angel investors, venture capitalists, technology accelerators and incubators, and private for- and non-profit firms. It includes entrepreneurs, small businesses, large corporations, policymakers, and ultimately, consumers. We are all playing multiple, often overlapping roles, participating in this ecosystem with our choices, our work, and our capital. Yet, for the most part, we operate without a common map or even a shared language.

Each year, the U.S. commercialization ecosystem is fueled by a massive and complex flow of capital. This represents a staggering combination of public and private resources aimed at bringing better solutions into the world. In fiscal year 2023 alone, the U.S. government provided over $1.2 trillion in financial assistance and U.S. businesses spent over $722 billion on R&D (USAspending.gov, NSF NCSES). This is complemented by the philanthropic sector, where foundations gave an estimated $103 billion in 2023 (Giving USA). All of this capital moves through the federal government, thousands of private sector entities, and over 100,000 private foundations (IRS Data), funding vital work at universities, national labs, non-profits, and countless companies.

The combined capital flows through thousands of distinct programs, each developed and run by a dedicated team with its own mandate, culture, and process. The challenge is that these teams mostly operate without a common language or shared playbook, creating an ecosystem in name only rather than a well-connected and informed web of organizations and funding. We all see a piece of the puzzle, and have some fellow practitioners we collaborate with, but none of us sees the whole picture. The result is a system defined by friction, gaps, and missed opportunities leading to ideas stalling at handoff points, capital sitting idle, and impact deferred.

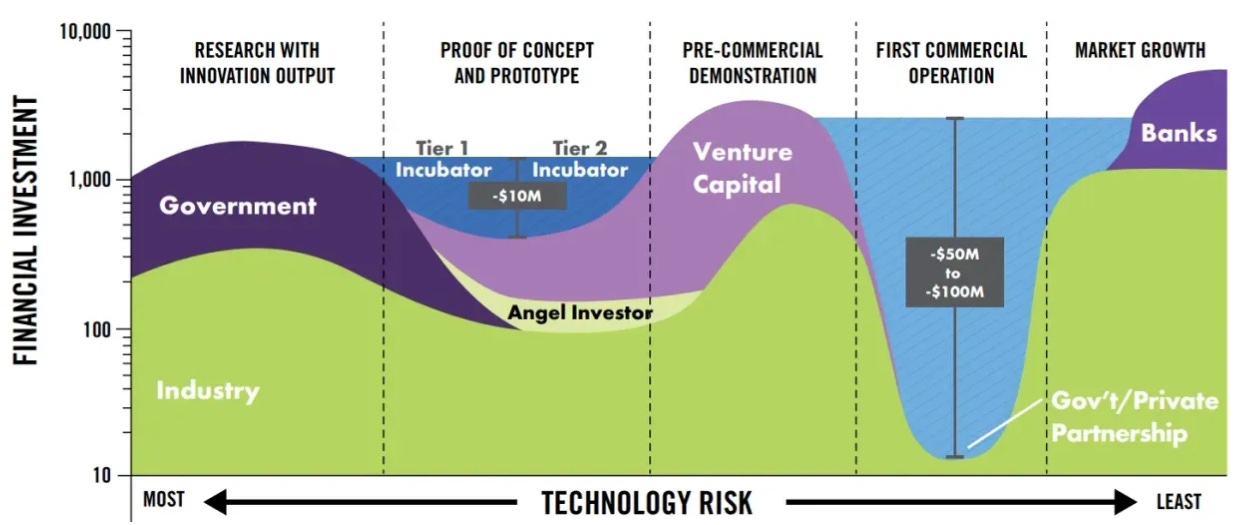

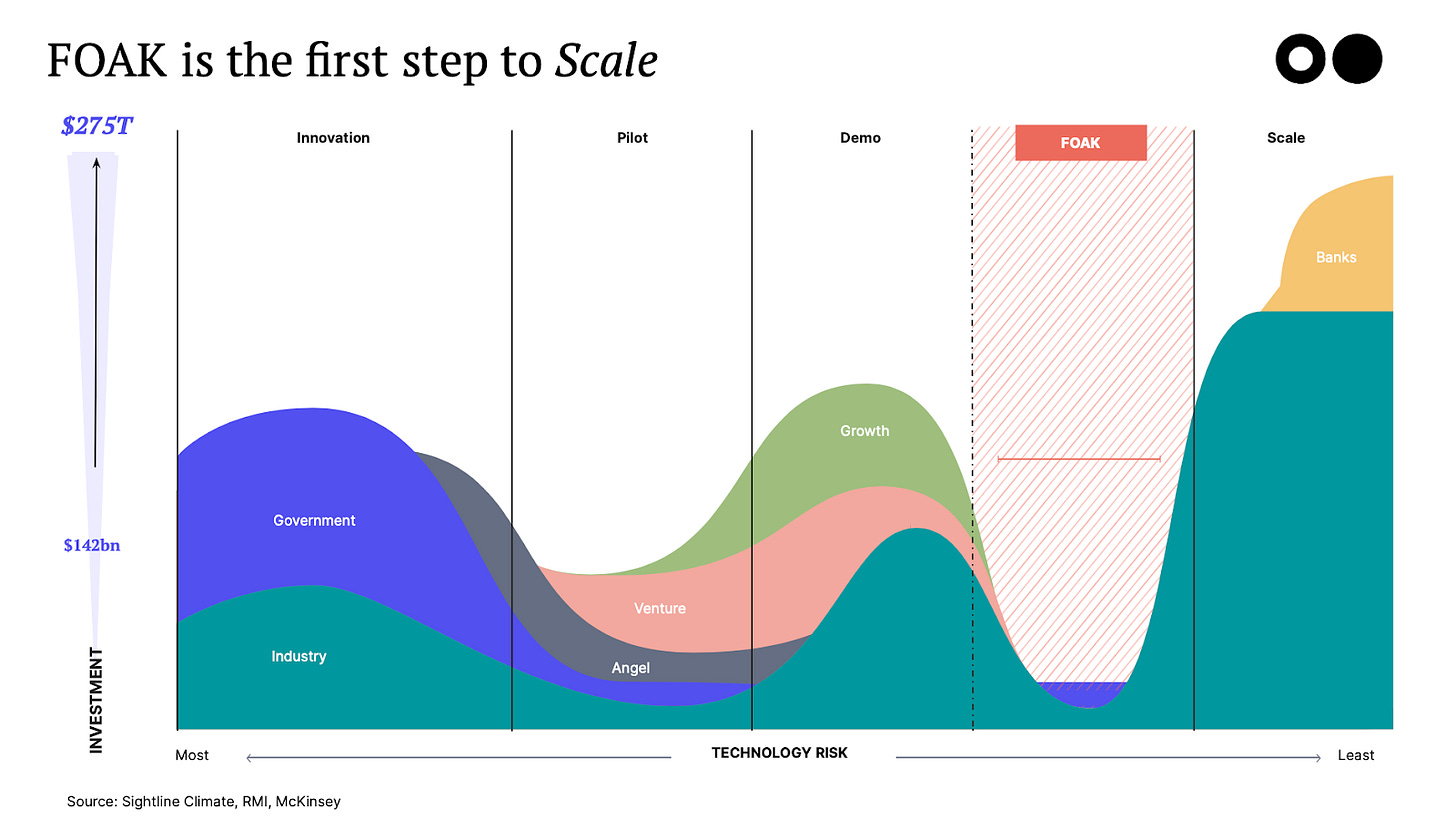

Below is an early image we developed in 2013 on the ecosystem gaps and the needs for programs like SunShot Incubator (which highlights the messiness of commercialization):

And this isn’t an outdated observation. A post by Sightline, 11 years later, highlights the same essential problems, focused on the ‘FOAK’ (First-of-a-Kind) capital gap. We’ve known the problems for decades, but progress still stalls. Similar ideas circulate and fail to be addressed due to the persistent coordination challenges we’ll discuss.

After spending decades collectively working within the US Department of Energy (DOE), one of the large nodes in this network deploying roughly 11.5% of government R&D funds in fiscal year 2023, we believe the greatest leverage for change lies not in finding more money, but in fundamentally rethinking the architecture of how we deploy it. We need to move from a collection of siloed, ad-hoc practices to a more intentional, coordinated approach. We need a shared language and a place to go to find and learn from each other.

As alluded to in our Introduction, we’re tackling three concepts in our first few series; Funding Mechanisms, Trust and Risk, and Commercialization and Ecosystems. This is our first in the Commercialization and Ecosystems series, starting with a framework we can all use and adapt: Full-Stack Funding Program Design.

The Craft of Capital Deployment: A Trade Learned Through Apprenticeship

Before we can build a better system, we must first understand how the current one operates. Learning to design and run a funding program, whether in government, philanthropy, or a corporate venture arm, is less a science and more a trade. It is a skill learned through years of apprenticeship, trial and error, and absorbing tacit knowledge that is rarely captured in a standard operating procedure or textbook.

For those who haven’t lived it, here is an example of how expertise in funding program design and implementation is obtained from Day 1 on the job in an organization like DOE:

Year 1: The Observer. You enter in the middle of a funding cycle. Programs are already live, others are under development, and multiple budget years are being debated simultaneously. Your instincts are often wrong. You quickly learn that logical arguments about process efficiency are not an effective tool for navigating the bureaucracy. Being a new member of a team, your technical comments are valued, but you have little to contribute to process discussions where the majority of the words are acronyms. You find a mentor and do your best to learn the ropes.

Year 2: The Contributor. Over the course of a year you have seen all the elements of a full funding cycle. You are helpful in planning meetings and understand jargon. You can accomplish many independent program implementation tasks, but you are not yet trusted to run one entirely on your own.

Year 3: The Manager. After seeing 1.5-2 full cycles, you can manage your own program from launch to completion. However, you aren’t yet able to truly innovate on the process, because you haven’t been assigned responsibility for the initial design choices and then seen how they play out years later.

Year 4: The Innovator. You now see beyond the obvious flaws that any newcomer might spot. Your experience allows you to identify the deeper, systemic limitations and propose viable alternative approaches. You push back on processes that are not optimized for the real world, and people start to listen instead of shutting you down. You begin to leverage new tools and approaches, adapting the model based on experience.

Year 5-9: The Expert. You have finally gained your footing. You are now an expert in most aspects of program design and implementation, and people come to you for advice. You understand not just the “how,” but the “why” behind the process.

Year 10: The Thought Leader. After a decade of running dozens of programs across multiple leadership personalities and priorities, your focus shifts from executing the process to fundamentally improving it. You have created and leveraged new tools and frameworks that are now used across the department. You are considered one of the people who can shape institutional efforts, not just individual programs. There are exceedingly few of these people, and many of them have left government service recently (present company included).

This apprenticeship model is slow and the knowledge it creates is fragile. High staff turnover constantly erodes this tacit expertise. Initially, this erosion just slows progress. The organization’s veterans are pulled away from designing better programs to field the same questions from ephemeral staff. Eventually, this erosion hits a tipping point. Once a critical mass of experts leaves, the institutional knowledge base collapses. It reverts to the next most experienced staff member or, in some cases, defaults to the bare minimum found in standard operating procedures, forcing the organization to relearn lessons that were once common knowledge.

This is not a failure of people; it is a failure of system design. Continuing to learn this critical craft by apprenticeship is a direct impediment to the speed and scale today’s challenges require. While this exact process and timing may not be the same for other organizations, at a high level, this order of operations plays out at funding organizations of all types and sizes.

From Ad Hoc Craft to Intentional Architecture: A Full-Stack Approach

The consequence of this craft-based approach is a system that is inefficient by default. The lack of a shared language and standard programmatic framework means that every handoff point (from a university lab to a seed investor, from a foundation prize to a government grant, etc.) is fraught with friction and translation errors. This is where “valleys of death” emerge, where promising innovations die not because they lack merit, but because they cannot navigate the gaps between disconnected funders.

This is not a failure of intent; everyone is working very hard to maximize the impact of their funding programs. But there is no shared playbook, so organizations and governments design new models they believe will be impactful, but they do so in isolation. Without access to collective lessons learned or institutional knowledge, they inadvertently repeat past mistakes. We lack the connective, data-driven tissue that could create a prosperous ecosystem, a gap caused by a simple lack of coordination and transparency about what is actually working.

To solve this, we need to shift our thinking from individual craft to a common but flexible program architecture. We need a common framework, and we borrow a term for this approach from the world of software development: full-stack.

In software, a “full-stack” engineer is someone who can build an entire application, from the user-facing front-end to the server and database on the back-end. The core idea is end-to-end responsibility for a complete, functional system. An innovation program fails for the same reason a software project does: its layers are disconnected. A brilliant outreach and engagement strategy (the front-end) is useless if the selection and funding process (the back-end) is broken.

This is the principle behind Full-Stack Funding Program Design: a methodology for architecting every layer of a funding program upfront so that resources, partnerships, processes, and outcomes stay aligned from launch to legacy. To introduce this framework, we’ll focus on its application to a single program. However, this approach is valuable, critically so, for designing and executing programs of programs as well. It can help define the interfaces and handoff points between different elements of the commercialization support ecosystem. By adopting a common framework and language, it becomes easier for diverse organizations to communicate and ensure a common understanding of objectives and approaches.

This is not a rigid, one-size-fits-all solution. It is a coherent operating system, a set of design principles that can be adapted by any organization that deploys capital for impact and can act as a basis for organizations to talk to one another about their programming and build stronger ecosystems of funding. It consists of eight integrated layers:

Thesis & Success Map - Every effective program begins with a clear and compelling purpose. This is the strategic anchor. It requires defining a sharp problem statement and painting a vivid picture of the desired outcome in three to ten years. This “success map” is then translated into phase-gated milestones that allow everyone in the ecosystem (applicants, reviewers, partners, and other funders) to understand what success looks like and how progress will be measured.

Ecosystem Scan & Coalition Building - A compelling program concept rarely exists in a vacuum. If your team sees a problem or opportunity, it’s likely others do too. This layer is about proactively mapping the external landscape to validate the thesis. It involves identifying potential partners, understanding competing or complementary efforts, and engaging stakeholders to refine your program’s focus. This critical step avoids redundant efforts, surfaces opportunities for collaboration, and ensures the program is designed to complement, not duplicate, the work of others.

In practice, this layer is often the first to be cut under pressure. This common shortcut is a massive missed opportunity. Arguably, no other step provides a more direct path to increasing impact by avoiding redundancy and building collaboration. This series will focus specifically on how to do this foundational work better.

Governance & Decision Ops - Trust and speed are built on clarity. This layer externalizes the decision-making process, turning it from a common cause of delay into a transparent workflow. It establishes a formal authority matrix, designs clear scoring rubrics, and creates auditable reviewer workflows. All engaged parties must agree and sign off prior to the program’s launch. When the process is visible and fair, it empowers staff to own processes and compress deadlines and decision makers to be decisive without fear from above.

Building Awareness - A world-class portfolio requires a world-class applicant pool. This layer moves beyond simple outreach to strategic brand and community building. It involves creating partner coalitions and providing robust applicant support to widen the talent funnel. The goal is to ensure the best teams with the best ideas are aware the funding exists and can compete on a level playing field.

Mechanism & Project Design - The funding instrument must fit the task. A simple grant is not always the right tool. This layer involves thoughtfully selecting a fit-for-purpose blend of mechanisms, such as tiered prizes for high-risk exploration, cooperative agreements for collaborative projects, or convertible vehicles for later-stage companies, to achieve specific R&D, demonstration, or deployment objectives.

Support-Service Layer - Capital alone is rarely sufficient to overcome real-world barriers. An integrated support layer surrounds awardees with the resources they need to convert dollars into progress. This includes practical tools like technical assistance vouchers for specialized services, access to mentor networks, assistance with policy navigation, and partnership brokering. This layer recognizes that de-risking a project often requires more than just money.

Budget & Timeline Architecture - In program execution, the calendar and the cash are not separate variables. This layer designs them as one integrated system to avoid predictable mid-stream cash crunches. It aligns funding tranches with realistic, milestone-based schedules that can quickly adjust if the world changes, ensuring capital is tied directly to verified progress and that program momentum is maintained.

Impact Verification & Feedback Loops - To be credible, impact must be verifiable. To improve, a system needs feedback. The final layer equips the program team with real-time dashboards to track progress, engages third-party evaluators to ensure objectivity, and establishes a rhythm for public storytelling and program iteration. These feedback loops are essential for demonstrating value, learning from experience, and unlocking follow-on funding and policy backing.

Now, most of you who work in this space are reading this and likely nodding along and thinking, “Yup, we do this already.” That’s the challenge. We have all found a way to solve for these needs, but what most of us have really done is find one way that works within our constraints. Very few of us have had the opportunity to truly optimize the full framework as a fully integrated system.

This is where our real opportunity for funding ecosystem collaboration lies. Every program has its center of gravity, a layer where it truly excels. For some, it’s a brilliant and flexible funding mechanism that attracts top-tier talent. For others, it’s an incredible support network that ensures awardees succeed. But because we all operate with finite resources and specific mandates, other layers of the framework are naturally less developed.

This isn’t a critique; it’s an invitation to build a shared playbook. Let’s talk openly about where our programs shine and where they face persistent challenges. What does success for each of these eight layers truly look like? How do you convince yourselves, and your funders, that the work you are doing is genuinely changing the world for the better? By speaking the same language and sharing what we know, we can help each other strengthen our individual programs and, more importantly, make the entire innovation ecosystem more effective for everyone.

Let’s Build This Together

This framework is not intended to be the final word, but the beginning of a conversation. The challenges facing our innovation ecosystem are not discrete; they are a tightly woven system where strategic intent is constrained by operational reality. Addressing one of these areas in isolation will yield only temporary, localized improvements. Lasting change requires a commitment to reforming the system as a whole.

Our goal in this series is to distill what we’ve learned into a shared knowledge base, a set of blueprints we can all use, critique, and improve upon. In the coming posts, we will dive deeper into each of these eight layers, providing concrete examples and lessons learned directly from the field.

The alternative to this work is predictable: more friction, more redundancy, and more effective solutions lost to turnover. The path we are proposing is a commitment to the less glamorous but far more vital work of stewardship. It’s time we build a system whose operations are as innovative as its science, creating a trusted and coordinated engine for our collective future.

Next up: A Deep Dive into Prizes

Innovation Waypoints is brought to you by Waypoint Strategy Group.