When Prizes Are the Wrong Tool

Understanding the boundaries of prize authority (Part 3)

In Part 1, we told the story of how prize authority at DOE went from dormant law to functioning tool. In Part 2, we walked through the full-stack design of the Solar Prize and how its success led to over 100 prize competitions across the agency. Both posts made the case for prizes as a powerful mechanism for reaching new innovators and supporting hard tech development.

This post is about when not to use them. The examples here come from DOE, but the lessons apply to anyone running prizes: foundations, corporate innovation teams, and private prize organizations face the same design choices.

The “Everything Should Be a Prize” Problem

When prizes started growing in popularity at DOE, an interesting thing happened. They were such a clear improvement over traditional processes in reaching new applicants that some started to wonder: why not just do everything with prizes? This was especially acute with new staff whose first program was a prize. When those initiated into funding design through the simplicity and logic of prizes were later confronted with the normal grant or contract process, they sometimes rejected it. And for good reason from their point of view. It feels unreasonable to subject applicants to so much more paperwork and process, negotiate every activity in advance, scrutinize invoices, and approve every dollar spent on the effort over years.

The issue is that prizes are not a suitable tool for all programs. Traditional funding mechanisms exist for a reason and incredible things have been done with them.

Mechanisms as Tools

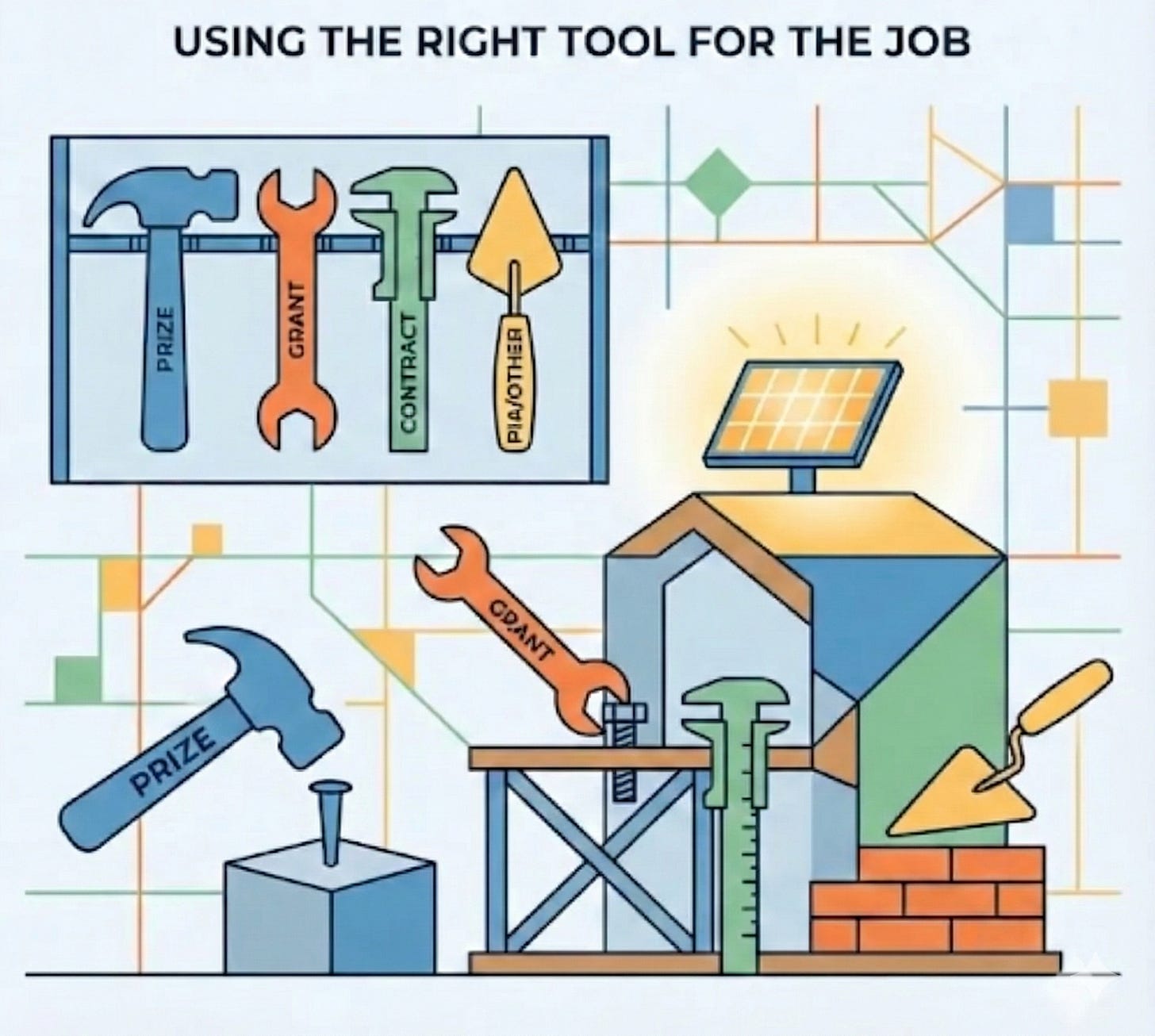

The way we like to think about funding mechanisms is as tools. In construction, a practitioner with an appropriate set of tools can build anything. With a saw, hammer, measuring tape, level, drill, and square, a house of any shape can be built, or a boat, or a boxcar. But if all you have is a hammer, your opportunity set is diminished because you end up using the wrong tool for the wrong job. Proper project planning requires knowing the strengths and weaknesses of each tool and when to use it.

So what are prizes good for? Prizes are competitions. They are a mostly passive tool to incentivize a community to activate around an issue and reward only those that generate the best results. Those that compete and don’t do well are out of luck. It’s intentionally selective and reductive. The most straightforward use is a well-defined, quantifiable technical challenge: the capability to make a widget that is 25% efficient doesn’t exist. If you make one and we can verify it, you get X dollars. Done.

You can add phases to support teams working on that challenge and spur more activity. This is still a good use of the tool. You can push one step further, as we did in the Solar Prize, and state that you want to create the best and most impactful two new solar startups once a year and give them $500,000 if they reach a legally binding customer commitment. This still works. Taking 100 to 200 competitors down to two with support services that help everyone along the way is still fundamentally a competition with clear winners.

Where It Goes Wrong

Where things go sideways is when funding program designers, with the best of intentions, seek to use prizes to make more and more awards for capacity building activities. Example: a disadvantaged community struggles to apply to traditional funding. The thinking goes, let’s do a prize to award them funds to do an activity, and then we’ll do multiple phases and everyone or most can win at each stage. These “everyone wins” prizes stretch the mechanism in ways that raise questions. At DOE, Congress noticed the agency was doing more activities like this and raised concerns. With sufficient concerns, the authority for the government to use prizes could be changed or eliminated.

The response to this criticism is that these communities can’t apply to traditional grants because it’s too difficult. Or that there just is not sufficient funding to support capacity building specifically - we expect new groups and applicants into our portfolios but have limited funds in building capacity to apply into funding. Prizes became a default tool to meet that gap, And that wasn’t without merit - until recently, there wasn’t a good answer to that argument. Now DOE has a tool that is a better fit for capacity building: the Partnership Intermediary Agreement. We hope to discuss the PIA mechanism in another post, but suffice it to say it offers a low barrier to entry, increases capacity building, and provides streamlined process without the competitive nature of prizes.

The Size Question

Prize amounts have to be motivating without being distorting. Too little and nobody bothers. Too much and perverse incentives emerge, or teams focused on trying to game the system for the money rather than the mission apply. The key is calibrating to the work required and the target audience.

One practical advantage of prizes is they work well for small awards. Traditional grant mechanisms struggle to make awards under $250,000 because the administrative overhead isn’t worth the return. The time spent on proposal review, negotiation, project management, invoicing, and closeout is roughly the same whether the award is $50,000 or $5 million. Program offices avoid small grants because they consume staff time that could support larger, higher-impact projects. Prizes have much lower overhead once the structure is set. The same competition that awards one $500,000 grand prize can also award twenty $25,000 early-stage prizes. The administrative burden doesn’t scale with the number of awards or the dollar amounts. This makes prizes particularly effective for early-stage support, where small amounts of flexible capital can make a material difference but would never justify a traditional grant process.

At the other end of the spectrum, very large prizes start to raise questions about whether a prize is the right tool. At a certain size, it becomes difficult to justify issuing a large, no-strings-attached award for a result when a cooperative agreement or grant would provide oversight and risk management over several years for that level of funding. The exact threshold isn’t clear, but somewhere between $1 million and $5 million, the calculus starts to shift. The administrative savings that make prizes attractive for small awards matter less when the stakes are high enough that active project management and regular check-ins would be prudent anyway.

That said, context matters. If a $5 million cash prize can catalyze $50 million in private investment, it could make sense. Which brings us back to a point we’ve made several times in this series: start with what you’re trying to accomplish, not with the mechanism you’re comfortable using. This is the Thesis & Success Map layer from our full-stack framework. What specific problem are you solving? What does success look like? What are the measurable outcomes that will tell you whether it worked? Those answers should drive the mechanism choice, not the other way around.

If you’ve never run a prize, finding the right program concept for your first one is especially important. If you’ve run many prizes, consider whether you’re developing tunnel vision. The tendency to default to what worked last time is natural but can lead to using the wrong tool for the job. This is a dynamic space. Paying attention to what others are learning and collaborating with practitioners facing similar challenges is the best way to avoid getting stuck.

With that framing in mind, here’s how we think about the boundaries:

When to Use Prizes

The sweet spot for prizes is well-defined technical or commercialization challenges. Specifically, situations where:

The path to success is uncertain and you want multiple approaches tried

You can objectively assess and judge results

Competition will drive innovation and urgency

You want to attract new solvers who wouldn’t normally engage with your organization’s funding

You’re facing an interdisciplinary issue that will require groups or scientific fields to tackle issues together

Winners can be clearly differentiated from non-winners

The work can be done on the competitor’s timeline and with their own resources (until they win)

When Not to Use Prizes

Conversely, prizes are the wrong tool in several situations:

Outcomes will improve from close funder oversight and active project management

The path to success is well-known and you just need someone to execute it

You need sustained, multi-year effort with regular check-ins and course corrections

You want to support capacity building or provide resources to help all participants

The goal is to fund many teams doing similar work rather than selecting the best

Success is subjective or difficult to judge objectively

A “winner takes all” dynamic would harm the ecosystem you’re trying to build

Conclusion

Understanding these boundaries matters beyond just program design. The lessons in this post come from an environment where prizes became popular enough that staff started using them for everything. That’s a good problem to have. It means the tool is well understood and accessible.

Outside government, the more common problem is the opposite. Prizes remain underutilized by foundations and private sector organizations that default to grants or contracts without considering whether a competition might work better. The same framework applies in both directions. If you’re reaching for prizes reflexively, ask whether another mechanism fits the problem better. If you’ve never seriously considered a prize, ask whether your current approach is actually optimal or just familiar.

Knowing the full toolkit, and being honest about which tool fits which job, is what separates effective program design from habit.

In Part 4, we’ll discuss what the broader prize ecosystem is missing and why the field needs a community of practice.

Innovation Waypoints is brought to you by Waypoint Strategy Group.